Tableland Tours | 19th Century

- Ray Salisbury

- Apr 16, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: May 23, 2020

While the miners scratched for a living in the desolate wilds of Northwest Nelson, and the musterers struggled to herd their flocks, another breed of visitor was seen on the Tableland: the tourist.

By the 1870s, people could take a mail coach from Nelson to Motueka, then private transport upriver. At various times, there were accommodation houses where weary travelers could stay, eat, and arrange pack horses to carry provisions for their journey. By the 1890s, it was possible to travel from Nelson to Pokororo in half a day by horse-drawn transport.

Technology and transport improved while society’s attitude toward the mountains began to improve.

A visitor in 1890 wrote:

‘I was a far better man in soul and body after inhaling the wondrous air of the Table Land.’

The most eloquent depiction is from the Nelson Guide Book & Directory, published in 1887. This booklet is dripping with sentimentality, painting the region as a type of Utopia for collectors of rock, bird, or flower.

‘The Tableland Trip: West of the snow-capped range, of which Mount Arthur stands the most prominent feature in the chain, lies the plateau known as the Table Land. To the active and able-bodied visitor to Motueka, this trip offers many inducements. To the residents of the sea-fronted, hill-backed, vale-sequestered town of Nelson, with its ever summer-like, but somewhat relaxing climate, the deliciously invigorating atmosphere of the plateau has always proved a most pleasant and beneficial revelation.’

Earlier, in 1879, Judge E.A.C. Thomas undertook an expedition where he spent the week sketching and painting the scenery on the Tableland. It was most likely the impetus for Nelson's second bishop to visit the plateau himself the following year. (Click on his sketches below for captions).

Bishop Suter's Tableland Tour | 1880

And so it was, in January of 1880, Bishop Andrew Suter, Reverend Mules, Reverend Grace, their wives, plus a large party of young people, set off from Nelson. The organiser was Edward Jennings, a theological student training under the bishop, who penned the written account of their camping holiday. It appears that he’d been working on the tracks over the previous years, so was pivotal in organising this trip.

Luggage was transported on the coastal scow Lady Barkly to Port Motueka, then up-river by horse and trap. This baggage consisted of blankets rolled up into swags with saddle straps, six tents, six flies, two fire-flies, with food, dishes, plus pannikins.

Traveling by various means, the group met up at Salisbury’s Ferry, 25km up the Motueka River, near the confluence with the Graham. The Salisbury’s old dugout waka was used to transport them across the notorious Motueka River.

Once across the river, John Park Salisbury offered the use of two pack horses and a bullock. The bishop’s riding horses were also taken. Finally, the travelers, numbering about 23, set off up the Graham Valley, camping 7km up the track. (Note that today's road wasn't completed until 1970.)

The Bishop’s huge party then laboured up the steep trail to Flora Saddle, accompanied by John Park Salisbury, his brother Thomas, and his teenage sons John and Ernest. These pioneers took charge of their animals, and ultimately, of the entire expedition. In mid-summer heat, they camped at Edwards Clearing, which the writer says was two acres; half hill, half level. (This is where Flora Hut was built in 1927.)

‘Thanks to Mr. John Salisbury’s supervision and bossing, the tents were pitched. He advised that raised bunks should be made for the ladies – which was an excellent idea and acted upon. The Flora was large enough for us to get very fair bathing, and almost cold enough to freeze one.’

About 3km further from where Flora Hut sits today, is where Andrew Suter apparently had a wash. Nicknamed Bishops Pool, it was a spring spraying over a high rock into a limpid pool.

Nineteen-year-old John Salisbury (Junior) guided the party across the boggy expanse of the Open, where the corduroy track was in a very bad state of repair. Crossing over the Tableland proper, the party set up their main campsite above Cundy Creek. In this sheltered, grassy clearing was a small double-ended cave, known since as Bishops Cave. John and Charles (possibly Rev. Charles Mules) went on a hunt for stray sheep, which proved successful, and provided mutton stew for many days.

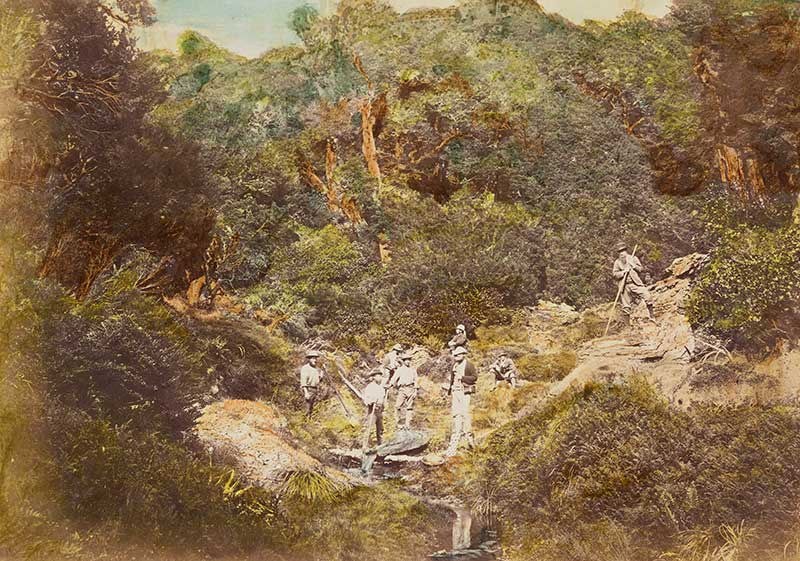

On the third day, the younger folk followed Cundy Creek down into the forested gully, which they called 'Dantes Wood.' Here, they entered a moa cave, igniting matches to light the way. They also visited ‘the hatter’ – possibly old Billy Lyons – and saw his claim, water race and dam.

An ascent of Mount Peel was enjoyed. Mrs. Amelia Suter and her horse were taken to the top, where a billy of snow was boiled over a fire. Following afternoon drinks on the summit, a lively snowball fight ensued – ladies versus gentlemen – which provided considerable amusement. Back at the campsite, a concert was held. A natural rock platform, about three metres high, was used as a stage. Eager faces looked up from the audience, peering through the darkness at each performer, illuminated by the flickering fire.

Next day, led by Thomas Salisbury, a mixed group of nine made a successful attempt on Mount Arthur, before regrouping with the main party to search for the stalactite caves, which Jennings describes:

‘The way to the caves led up a long, open valley, wet in places and tiring to walk upon, over a low wooded saddle, and down to the end – about three miles in all.’ From this description, it is probable they entered Pillar Cave. ‘It is the peculiarity of the creeks here running into, not out of, the hills. We did not go much past the first chamber, which, when lit up with magnesium lights, was very beautiful. Thousands of glittering white stalactites hung from the roof above, which was dome-shaped and about twenty foot high. At the side, many of the stalactites had joined with the stalagmites and looked like marble pillars.’

In his newspaper report, A. Dalesman noted that they resisted the urge to deface the stalactites, something that later groups were guilty of. Another visitor boasted:

‘I stoutly objected to affixing my own name on any part of the wonderful whiteness, although unhappily I saw precedents in my predecessors to the caves: for quite an array of daubed pencilings sullied the virgin purity of the incomparable in whose glorious sheen cannot be described.’

After singing a round inside the small cavern, the trampers returned to their campsite. After supper, the crowd assembled for another concert. It is heart-warming to read that they invited the local diggers, plus their packmen, then got them to participate.

‘A written programme had been drawn up for the evening. The Bishop gave a short story; Mr Grace a Māori haka in costume; Charles gave a recitation; the rest consisted of … solos and duets; the brothers Hodge ascended the stage and gave us ‘Picture on the Wall.’ After prayers, they left.’

Being a religious group, Sunday was observed with a service. On that evening, they enjoyed singing ad libitum – every hymn that was suggested was sung. This Bishop sang from the platform, and Thomas sang an anthem. The singing continued into the night; no one wanted to retire.

It is interesting to note that their guide, 47-year-old Thomas Salisbury, got involved with this concert. It was only thirteen years since he had found the Tableland, and Jennings mentions (and therefore validates) this discovery, calling him ‘a true specimen of a gentleman digger.’

As the expedition came to a close, falling rain failed to dampen spirits, as the troupe headed back toward their camp in the Flora, then down, down, down, to the Motueka valley below.

(Interestingly, the writer of this report, Edward Jennings, married one of the lasses three years later. He got ordained and, later in life, became a headmaster of a private school in Gisborne.)

A month after their alpine adventure, all the participants of this trip were invited to Bishopdale for a reunion. The bishop had composed a song, which they sang to the tune of My Mary Land. (See end of blog post for lyrics.)

Brereton Family Expedition | 1882

In the year 1882, the Breretons left their farm in Pokororo on a pilgrimage up the narrow trail over Flora Saddle. The father carried a heavy swag, followed by four of his children, including six-year-old Cyprian. Camping in the Flora for the first night, the youngster was immersed in his first back country experience.

‘We were interested in the weird birch trees, like old men, stunted, gnarled and distorted in their long struggle with the storms. The snow had twisted their trunks and bent their branches into fantastic shapes.’

The next morning, the family moved on to stay inside Salisbury’s hut, which was a stone’s throw from the Dry Rock Shelter. Cyprian reckoned that John Park Salisbury stayed under this overhanging rock while he built his mustering hut nearby, in proximity to the nearest water supply at Salisbury Creek and within view of his flock. (This whare was later used by Henry Washbourn in 1883, and George Hudson in 1889.) Cyprian clearly remembers the whare was in poor condition in 1882:

‘The hut was falling into disrepair and was seldom used afterwards, mostly because it was flea-infested with particularly ravenous insects.’

Sadly, the close-knit family was grief-stricken when father and son Jack drowned in a boating accident off the Abel Tasman coast in 1890. Brereton Cove was named in their honour. Young Cyprian then had to manage the farm at the tender age of fourteen. In later life, he penned the local history in No Roll Of Drums, and was the curator of Nelson's museum for about 30 years.

The Tableland Song | by Bishop Andrew Suter | 1880

A voice from Motueka’s shore The Table Land; the Table Land. A Tryst at Mrs Fearon’s door The Table Land; the Table Land. Some twenty people less or more Like some gay pilgrimage of yore So many ne’er were seen before On the Table Land; the Table Land.

Chorus: Of Nelson’s highlands far the best The Table Land; the Table Land. In beauty passing all the rest The Table Land; the Table Land.

‘Tis high above all Nelson so The Table Land; the Table Land. Four thousand feet you’ll have to go The Table Land; the Table Land. For there the rush and mistletoe, The lichen and the red birch grow The rata and koromiko On the Table Land; the Table Land.

Mrs Suter, Mr and Mrs Mules The Table Land; the Table Land. The Bishop, all with their reticules The Table Land; the Table Land. As blithe as girls escaped from schools No sleep nor slough their ardour cools ‘Tis the Reverend T.S. Grace that rules The Table Land; the Table Land.

Down looks on thee Mt. Arthur’s chain The Table Land; the Table Land. Which ladies won’t attempt in vain The Table Land; the Table Land. We look up daily from the plain And wish that we were there again On hills reflected in the main The Table Land; the Table Land.

I welcome your feedback, so feel free to leave comments below.

Read more in Ray's 70,000-word book titled Tableland - the history behind Mount Arthur. The coffee-table-style book is to be published by Potton & Burton in October 2020. See special offer below.

Comments